Introduction

'Dales, Plants and Gardens 1900-1960' is a project collecting information about cottage gardens in the North Yorkshire Dales of Swaledale, Arkengarthdale and Wensleydale; collectively known as The Three Dales. We are recording older dales people talking about the gardens that they remember, often from their childhood. Our focus is on the food plants grown and gathered from the wild, and how they were grown, stored and used. From these memories three publicly accessible gardens have been created by volunteers to be used as workshops for children and adults today. Understanding husbandry techniques and food plants that work best in the climate, altitude and soils of the northern Pennine dales of Yorkshire will ensure local food security in the future. The Three Dales are primarily a pastoral economy.Many dales families continue to live and work in the same areas that their families always have. Memories are long and farming people are conservative, and so we made 1900 our start date. 1960 is an arbitrary end date. Some of the influences that make 1960 the project's end date include: a marked increase in second-home ownership, the increased use of plastic flowerpots, and the installing of television in homes only recently connected to electricity.

Terrain

U-shaped valley with drumlins, fells and moors with limestone scarsWensleydale is a dale of grass, stone and water. Drumlins, glacial deposits soft-mounded under their duvet cover of grass, litter the valley floor. Cattle graze the ings or flood meadows created by the meandering River Ure. Pastures, improved since the 18th century, provide rich silage to feed livestock over the winter. Further up the valley slopes, hay meadows tapestried with wild flowers and humming with insects dot the landscape. On the moor tops, particularly between Wensleydale and Swaledale, lead mining and stone quarrying industries intermingle with lines of grouse butts.

Geology

Wensleydale is part of the same geological system as Swaledale. The Great Scar limestone is overlain by the Yoredale series of rocks; the series are a rhythmic succession of limestone, shale and sandstone. Erosion has created distinctive step-like terraces along the valley sides. This is clearly seen in Wensleydale where the hard limestone scars stand out like the risers of a giant staircase with the easily weathered shales as the treads.

Both Wensleydale and Swaledale run from west to east. Upper Wensleydale is indistinguishable from upper Swaledale. When crossing the Buttertubs, a pass between the two dales, it's hard to know where one dale ends and the other begins, but there the comparison ends. Mid-Wensleydale is a classic U-shaped valley, easily recognisable from school geography lessons. The River Ure meanders peacefully across the valley floor, whereas the valley of Swaledale twists and turns with its fast-flowing River Swale.

Climate

The climate in Wensleydale is similar to that of Swaledale; cold southwest winds howl through them both. If plants are to be grown then walls are essential to protect them and those who husband them. Winters are long and cold and the growing season short. On her journey through England and Wales Celia Fiennes wrote:

"... in these Northern Countyes they have only the summer graine as barley oates peas beans and lentils noe wheate or rhye, for they are so cold and late in their yeare they cannot venture at that sort of tillage, so have none"(Celia Fiennes, The Journeys of Celia Fiennes [1685-1703], ed. Christopher Morris 1947, London).

The cost of feeding livestock through the winter can be prohibitive. Farmers rely on the hay and silage that they can make in the summer and rent land lower down the dale rather than buy in extra fodder if they run short. Mid-season vegetables work better than trying for an early season or extending late into the year.

Hay meadows

The Anglo-Saxons were probably the first farmers to introduce the technique of hay making to the North Yorkshire Dales. Traditionally, meadows are grazed through winter and spring by sheep and cattle and cut for hay in the summer, after which the animals are returned to graze on the ‘fog' or stubble. Only the dung from the grazing animals fertilizes the ground. No pesticides are used on the meadows; instead parasitic plants such as yellow rattle weaken coarse grasses. It can take up to one hundred years to create a hay meadow rich in delicate grasses and wild flowers. Such a meadow can be destroyed in a couple of years by adding artificial fertilizers and cutting at the wrong time of year. Hay meadows are now scarce and protected by Natural England, the environmental arm of DEFRA.

Traditionally managed hay meadows were once common throughout Britain. Today they are rare, only a thousand hectares remain mainly in NorthYorkshire, Northumberland, the Lake District and the Border country of Scotland. The meadows are grazed and dunged by sheep and cows through the winter and spring and then closed to the animals in May, the sward growing until ready for cutting in June or July.

Grass for grazing dairy cattle in particular was so important to the economy of Wensleydale that many of the people that we've interviewed about growing vegetables said that they neither had the time nor the inclination. Managing the land on which to raise dairy cattle was of more importance.

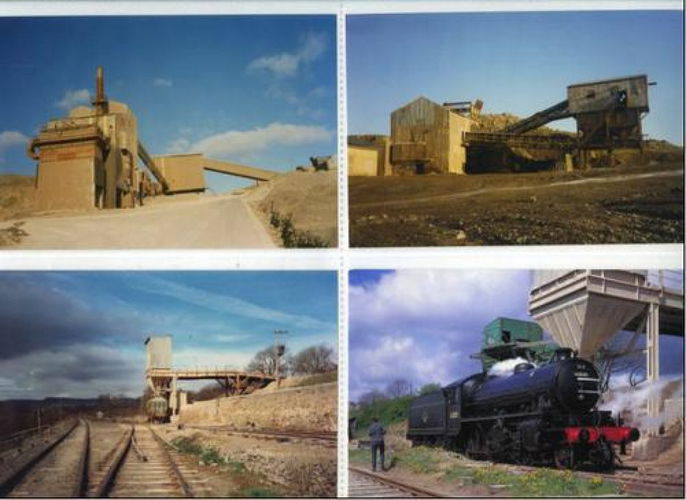

Lead mining and Stone quarrying

The moors between Swaledale and Wensleydale are full of disused lead mines: Cobscar, Virgin, Sargill, Wetgroves and Keldheads. To plant crops, stones have to be removed from the ground, so rather than plant hedges, dry-stone walls were built without mortar and have separated fields for thousands of years. Everything in the dale was built using the local stone. Wensleydale's railway was built to shift huge amounts of stone quarried from the moors to build the cities that have risen around the dale.

Meadowland and industry have always been kept physically separate in Wensleydale, although they were often worked by the same families. Grass was grown on the valley bottom and the lower slopes of the dale whilst industry was placed on the moors with their poorer soils but richer veins of minerals and stone. Industry has shared the heather moors with the grouse and those who care for them and shoot them since the 19th century.

Lead mining in particular has had a major effect on the look of the North Yorkshire Dales. Spoil-heaps from the 19th century are still so toxic that few plants grow on them; those that do form unique colonies of plant species that can tolerate the presence of heavy metals. Metallophytes are a group of plants that can tolerate the low levels of nutrients due to leaching, recent disturbances due to any re-working of material and the high concentrations of heavy metals. The plants that can be seen growing on the lead spoil heaps include spring sandwort, sheep's fescue, alpine pennycress, Pyrenean scurvygrass and thrift (more commonly seen growing in coastal conditions). None of these species are unique to lead mining spoil, however, together they do form a unique group of plants in Wensleydale.

- Visitor Access, Directions & Contacts

Telephone

01969 666210Access contact details

Although much of the countryside in Wensleydale is designated as open access under the Countryside and Rights of Way Act, the individual gardens are all private property. Please do not trespass.

- History

Wensleydale, like Swaledale and Arkengarthdale can seem empty to outsiders. There are neither sizeable towns nor acres of industrial units and factories; of the two main roads through the dale one doesn't even have a road number. Yet every acre of land has either been or is still being intensively used. Throughout the centuries successive tribes have made their farms in Wensleydale. The Norsemen entering the dale with their sheep from the west found the fells similar to their homelands. The Angles and Saxons entered from the east end of the dale bringing farming techniques such as ploughing with oxen and crop rotation. The Normans in the 11th century invaded the dale with a scorched earth policy, ‘Harrying of the North' and turned Anglo-Saxon farmland held in common into hunting forests for the privileged.

The dale's U-shaped valley has a wide flood plain, its ings or water meadows, enriched by silt from the meandering River Ure, create the lush grassland on which dairy cattle have fed for centuries. Hefted sheep have roamed across the moor tops since at least the 6th century. They are bought and sold with the farm, ewes being returned to the moors as soon as possible after lambing to instill territorial grazing knowledge into the next generation. No fencing is needed, instead the shepherd and his dogs regularly visit the flock and remind them which side of the stream or ridge is theirs.

Fellsides and Moor-tops

Lead miners were keen smallholders, renting a few acres up on the moors, mainly those bordering Swaledale such as Keldheads, Cobscar, Virgin and Wetgroves. They were limited in what they could grow and what livestock they could keep due to lack of naturally available fodder, the thin peaty soil and their remoteness from anywhere. So great was the demand for land to rent that even marginal land high on the moors was keenly sought after by them: "... all grass enclosures are rich and let very high".

Being self-employed the lead-miners were able to set their own hours of work, leaving themselves not only time to work at their smallholdings but also at seasonal tasks such as haymaking and shepherding. The miners rarely kept pig and hens as they ate the same food as the other miners and their families ate: potatoes, cabbages and oatmeal.

Valley bottom

Unlike the miners and quarrymen, most farming families had neither the time nor the inclination for gardening; if it was done at all it was by the farmer's wife. Grass, its quality, availability and management, is the plant that absorbed the minds of cattle farmers. There was money to buy fresh produce either at the local market where they went weekly to sell livestock and hire labour or it was bought from traders who drove round the dales with their goods.

Dairy cattle formed the wealth of Wensleydale's yeoman farmers. In the 17th century, when English wool prices began to fall, farmers turned from sheep to cattle. They had little capital but large families, ideal for the many tasks in dairy farming. Their farms were not large, ranging in size from 50 to 100 acres, with incomes "rarely amounting to £150 per annum". This was poor by comparison with a few estates in other parts of North Yorkshire, with incomes of over £30,000, but a comfortable, middle-class living compared to sheep farming.

Wensleydale's shape - a flat valley bottom rising to soft curving fells by way of terraces of rock - made it possible to run first a turnpike road and later a railway between the dale and the industrial cities of Lancashire and the East Riding. Access to the rapidly growing cities meant a rapidly expanding market not only for Wensleydale's products such as cheese, butter, hay, stone and lead but also for its labour. Unlike the populations of Swaledale and Arkengarthdale that of Wensleydale didn't decrease significantly when the mines closed at the end of the 19th century. The mining families of Wensleydale could either seek work in the cities close by or in the dale's mills, for instance at Gayle, Burtersett or Appersett. Entrepreneurs, depending on economic fashion, turned corn mills into spinning, cotton, silk and paper mills. (For the families of Swaledale and Arkengarthdale, the only hope for earning a living frequently meant emigrating to North America.)

In the 18th century fat cattle were driven on turnpike roads across the Northern Pennines, and milk, preserved as cheese, was carried to the rapidly expanding cities of Lancashire and the West Riding. When the railway opened in 1878 so to did the market for Wensleydale's fresh milk. Today the railway has gone, but since the end of WWII and the creation of the Yorkshire Dales National Park tourists have continued to use the old roads into the dale, significantly contributing to Wensleydale's economy.

Fishing and hunting with guns, dogs, on foot and horseback have always been popular in the Northern Dales, as have various less orthodox methods such as lamping, ratting and ferreting.

The first people to race horses were the monks in the 13th century, their monastic centres are still home to race meetings today in Ripon, Thirsk, York and Catterick, and training stables in Wensleydale at Middleham, West Witton and Coverdale. Pigeon racing has also been popular since the mid-19th century. They were kept in allotment sheds next to the pig, hens, cabbages, peas and potatoes, though today Health and Safety rules prohibit the pig.

Wensleydale, like all the Northern Dales is not as empty as it first seems to outsiders. In partnership with the large estates managing grouse, the Ministry of Defence and the hill farmers hefting sheep, hunting rabbits with ferrets and mole-catching preserves the flowers and delicate grasses of the moors and fells that are now celebrated by the Yorkshire Dales National Park and Natural England.

Over the centuries quarrymen and miners have trodden the same flowers and grasses on their way up to the mines and quarries that shepherds and dairy farmers have relied on for their livestock. The sheep are still on the fells, just, but dairy farming has almost disappeared due to Foot and Mouth disease and increasingly restrictive regulations. The only quarry of any size still working is at Redmire and there have been no working lead mines since the end of the 19th century. The Yorkshire Dales National Park Authority is now the major regulator of how the land is managed, and that is for tourism. For most of the year only ramblers and soldiers on training exercises march across the moors along with the sheep; though from August guns shooting grouse still punctuate the air as they did in the 19th century.

- Features & Designations

Designations

National Park

Plant Environment

Environment

Features

- Planting

- Artefact

- Key Information

Type

Garden

Purpose

Horticultural

Plant Environment

Environment

Principal Building

Agriculture And Subsistence

Survival

Part: ground/below ground level remains

Open to the public

Yes

- References

References

Contributors

Sally Reckert